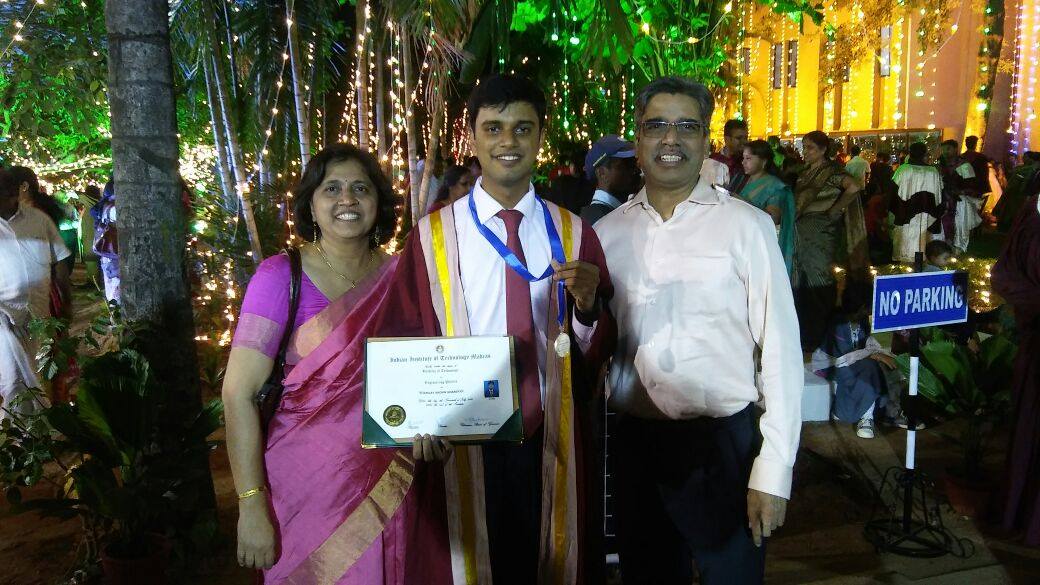

Prof V. Kamakoti, project coordinator at IIT Madras for the Shakti Project and chairperson of India’s AI task force

Source : http://shakti.org.in/media.html

In August 2018, media reports were flooded with “Shakti” – the first-ever indigenous microprocessor to be designed by a team from IIT Madras. The highlight of the microprocessor is that it is based on an open-source architecture which makes it accessible to everyone free of cost.

Shakti was a very ambitious academic project which was successfully executed within a relatively short duration while opening up many vibrant possibilities in the future not only in academia but for industries as well. The brains behind this product are none other than the RISE (Reconfigurable and Intelligent Systems Engineering) group from Department of Computer Science, IIT Madras headed by Prof. V. Kamakoti working on the areas of Computer Architecture, Security, Machine Learning and VLSI Design.

T5E sat down with Prof. V Kamakoti to discuss the venture, Shakti.

T5E: How were you inspired to start something of this scale?

Electronics play an integral role in our lives; they’re ubiquitous! When you buy hardware – like a computer, there are some electronic components inside which makes it work. The electronic components are programmable, which means you can tell this electronic component through the programs you write to do whatever you want it to do. This programmable electronic component inside any electronic system is called a processor.

If microprocessors that you buy are black boxes that come from foreign countries, then we don’t quite know how it will work. We can confirm that it does what we want to do, but we will never be in a position to confirm it doesn’t do what we don’t want it to do.

A microprocessor is the brain of all the electronic hardware in your deployment. If this microprocessor is imported and it is a black box, there is always a possibility that it will do something we don’t want it to do and that can be detrimental. So, as electronics becomes very close to us, every country should have its own indigenous microprocessor.

In 2012, we recognised this and kick-started this program to develop a microprocessor which can be used by all Indian startups and Indian strategic programs.

Power in Sanskrit is Shakti. That’s how we came with the name Shakti.

T5E: What is the significance behind the name of the processor?

The first open-source processor was from IBM called POWER. We wanted to take that and start making chips out of it. It’s called Open POWER. Power in Sanskrit is Shakti. That’s how we came with the name Shakti.

T5E: How was this project conceptualised?

When we started analysing this open POWER, it was not as open as we thought. There were a lot of lines, a lot of legacies we needed to learn and it never brought us anywhere close to our goal. This didn’t fit into our type of academic work.

At that time, Berkley and MIT started an open-source RISC-V consortium. RISC-V is an open-source hardware instruction set architecture (ISA) based on established reduced instruction set computer (RISC) principles. They heard about our idea for an indigenous processor for India. A collaboration ensued, and we became one of the early founding members of the RISC-V foundation. It is known as Open Source Instruction Set Architecture. It is defined as the open-source definition of what a processor will do.

We took that open source definition, and we started creating Shakti class of processors. This program is not just to make a processor, but also to develop a processor ecosystem in the country.

We are looking at all aspects from designing the chip, manufacturing, assembling it on to a PCB (Printed Circuit Board) and validating it. We wanted all three phases, design, fabrication, validation, to be done in India. The design was done at RISE lab, Department of Computer Science, IIT Madras, the fabrication was done at the Semiconductor Laboratory, Chandigarh with 180nm technology and the validation by making the whole motherboard at IITM.

That was one attempt.

Next, in collaboration with Intel, another chip designed in IITM was fabricated in Oregon with 22nm low power technology. This feat of fabricating two chips was done within a short duration of six months and was successful both times. The credit goes to the entire team of my students and project staff.

T5E: Do you think the existing infrastructure in our country for fabrication limits the extent of what more could be done with Shakti?

Yes, in terms of frequency, we can do up to 100 MHz as that’s the best 180nm can offer. There are specific small enhancements that a fab does like putting the clock on the chip which currently they don’t have. Then we can increase it to 150-200 MHz. That’s the maximum we can do in 180nm technology.

The facility to fabricate does not exist in the institute. As per the specifications of the processor, we will currently be collaborating with SCL at Chandigarh. In the future, as per requirements, we can work with Global Foundries, TSMC, Taiwan or Samsung.

T5E: When you say open source, it means other people can also modify the source code. How is security ensured?

The language used to design the processor was Bluespec System Verilog (a hardware description programming language). The design of all the processors is available on shakti.org.in under a BSD (Berkeley Software Distribution) license where anybody can source it, modify it and they needn’t tell us what they have done. When a product is an open-source product, there are different licensing norms like a GPL or BSD license. With GPL (GNU General Public License), any modifications required are to be reported. Under a BSD license, this isn’t needed. If you are a strategic agency, you are welcome to take this, and you need not tell us what you did with this.

The reason why we are releasing it as an open-source product is because we need wide acceptability and we want many customers to start using it. We want Indian startups to commercialise their products using this. Once it is successful, we can push it forward. For strategic agencies, we can customise it, and we believe that it is secure.

Today we are working for many strategic agencies, and each strategic agency requires different types of functionality. I can take one fundamental design, customise it and give them the desired designs back, which makes life easier.

T5E: How was the initiative funded?

The institute supports the initiative in terms of space etc. My group received a grant of around 11 crores from MeitY. We have written another nine crore proposal that we will get soon. An alumnus, Mr Pratap Subramaniyam, has sponsored about 1 million USD for opening up a centre called C-DISHA.

A start-up like this is an opportunity for India to leverage the open-source platform and commercialise customising open source for different agencies.

T5E: What are the goals of the startup Incore Semiconductors?

The startup is run entirely by the students. A start-up like this is an opportunity for India to leverage the open-source platform and commercialise customising open source for different agencies.

The idea behind the startup model is that a royalty-free open-source processor is available. A startup can customise, monetise and maintain it for a client. The students want to demonstrate how a startup can survive in this ecosystem.

T5E: This has been a long project spanning almost half a decade. There must have been both highs and lows. Would you like to share the team overcome any setbacks?

The main challenge was that we were new to everything!

We have not fabricated a microprocessor from IIT. We have fabricated very small chips in comparison to a microprocessor. Getting a microprocessor up and running the LINUX was the biggest challenge.

Now if you ask us to make a chip, it’s child’s play. We know what it is. We have had two experiences, and both were excruciatingly complex. It took us a number of days to get that thing up, and that’s a story for another day. On the other hand, now that we have learnt many things, things have become very smooth for the next step. We have learnt all the lessons, and that was a very interesting experience.

As a faculty, I feel that my experiences would be incomplete had I not taken up this work. Now I feel that I really understand and know what to teach, what to set in a question paper, and what the students have to learn.

Nothing that I taught would have anywhere helped anybody in a tangible sense to execute a project of this sort.

I reflected upon all that I taught in the area of architecture and organization in Computer Science for the past 16 years before this experience. Nothing that I taught would have anywhere helped anybody in a tangible sense to execute a project of this sort. That is the academia-industry gap. There are some high-level concepts like pipelining, for example, on which I have published a lot of papers but when all those things have to be implemented from paper to wafer, it’s a different ball game.

The biggest revelation has been the way I view Computer Science, and specifically Computer Architecture now. I have been teaching Operating Systems for the past 20 years. I never realized that before the boot prompt comes, 72 million instructions are executed. These are some things which are very thought provoking and interesting. When RISC-V came up, within two weeks of MIT and Berkeley announcing their own chipsets, we had Shakti. For at least 6-7 months, we had the lowest power RISC-V chip in the world. Every faculty and student should go out for the tape-out experience (the final result of the design process). Working from the ground up makes everything very interesting, and there are many lessons to be learnt. I continue to learn from this practical experience, and I believe it’ll make me a better teacher. I always believed that Education is a progressive way of discovering our ignorance. The SHAKTI project reassured my belief.

The interaction with Prof. Kamakoti was a great eye-opener into the journey of Shakti, which has intrigued all of us for a long time. At the end of the day, the motivation to provide a secure ecosystem for all the home-grown industries as well as the perseverance to achieve something generally perceived as almost impossible is what makes the team stand apart and makes them worthy of our adulation.

Science Deconstructed is a series which aims to introduce some exciting advancements made by the scientific community in simple terms with guidance on how to pursue these fields in the institute, along with features of research by groups in the institute. Send in your requests for the same at [email protected]. Suggestions/ comments are always welcome.

Series by: Sankalpa Venkatraghavan

This article really brought some energy into me. I’m enchanted with the idea of developing a processor ecosystem in our country. And I look forward to seeing more of such revolutionary ideas which would help bridging the gaps between academia and industry in India.